Sentiment Analysis on a Micro Server

Published:

Reading time: 5 minutes

Where’d you get the idea, Matt?

Data scientists are expected to do more than simply clean data, explore the data, and build a model that fits the data well. Once a model is obtained, it has to be consumable in some way for a target end user. I’ve never had the opportunity to build an online API for accessing a model, so I decided to take a simple problem with a simple solution and try to get it accessible online.

Outline

The goal is simple: from Kaggle’s dataset consisting of 50k Netflix reviews, paired with the rating associated with the review, can we make predictions about the general sentiment of a newly written review?

In what follows I’ll give an overview of the steps involved:

- Converting a review into a machine-readable format using a bag-of-words model

- Fitting the bag-of-words to a logistic regression

- Deploying the model to a server (AWS EC2-instance micro)

- Setting up interactivity

1. A Bag of Words

The first step in converting a block of text into a machine-readable format is to “tokenize” each important chunk of the string. The simplest thing you can do is break up a string into words, and convert each word into an integer. So the string “The fat cat sat on another cat” could be tokenized to a list of integers [0,1,2,3,4,5,2] through a dictionary {“the” : 0, “fat” : 1, “cat” : 2 “sat” : 3, “on” : 4, “another” : 5}. If I train my tokenizer on more documents, the vocabulary grows, so I might also have {“dog”:6, “ate”:7, “my”:8, “homework”:9} in the vocabulary after training on another string.

Some additional things to think about are how to deal with punctuation, or accented characters like ç, or which words shouldn’t be included in the vocabulary. I’ve used a tokenizer which converts all accented characters into their non-accented ASCII relatives, and which treats punctuation like a space. I’ve also used an exclusion list to remove common words from the vocabulary that shouldn’t affect the rating of a review – words like “the”, “a”, and “and” – since these don’t add information about whether a review was good or bad.

Now that the words are machine-readable, we have to decide how to encode an entire review. To keep it really simple I’ve used a bag of words model, which throws away all positional information of each word, and instead simply counts how often each word appears in a document. The example above would generate a bag of words {0:1, 1:1, 2:2, 3:1, 4:1, 5:1, 6:0, 7:0, 8:0, 9:0}, i.e. the word “the” appeared once, the word “cat” appeared twice, and the word “dog” appeared zero times. Usually though, the bag-of-words is implemented as a sparse array, which only includes the non-zero entries.

We can further choose to keep some positional information: the vocabulary can be extended to include two-word chunks, so that the string “the cat” get its own token. This is important for situations like the string “not great”, where “not” doesn’t have much meaning by itself, “great” is a strong positive word, while the two together “not great” is moderately negative. I chose to have my vocabulary include only 1- and 2-word tokens.

My first instinct was to use scikit-learn’s TfidfVectorizer to implement the bag-of-words model. This model is a combination of the CountVectorizer, which counts the number of tokens in a review as described above, but also uses the “Term Frequency x Inverse Document Frequency” to normalize the counts of each token so that the review length isn’t a factor for inference.

However, the TfidfVectorizer has to store a dictionary representing its vocabulary. When trained across 50K reviews, while including single- and double-words, the size of the model reached around 500MB (shoutout to the asizeof package for letting me see how much memory a class instance is actually using). My AWS EC2 micro-instance only has 500MB of memory, so deploying such a large vocabulary to such a small server is out of the question.

Enter the HashingVectorizer. This class does essentially the same thing as the TfidfVectorizer, except it doesn’t store a vocabulary at all; rather, it algorithmically hashes each allowable single- or double-word into a token. With a large enough state space (I chose 2**18), hash collisions should be a very rare occurrence. asizeof shows that the size of a HashingVectorizer instance is only 4.1KB, which is great!

2. Logistic Regression

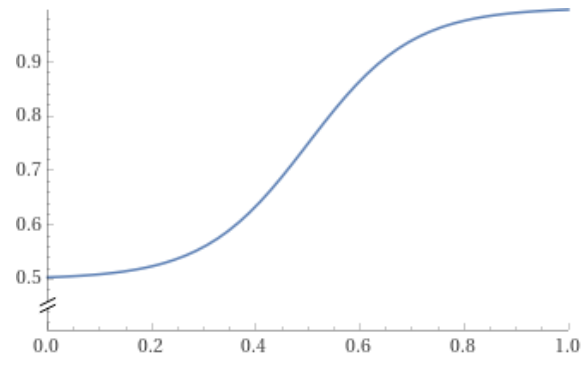

If you’re reading a review and notice that the word “terrible” appears very often, it’s likely that the author didn’t think very much of the movie. By contrast, a review that says “amazing” over and over probably thinks pretty highly of the movie. If you see neither of these words, the author probably just has a different vocabulary and so you should be looking at other words for information; based on these words alone, the probability of it being a good review probably sits around 50%.

A common way to describe the probability curve like this is based off the logistic function,

$f(x) = \frac{1}{1+\exp(-(x-x_0)/w)}$

where $f_0$ is the probability at the far-left of the distribution, $f_0 + H$ is the probability at the far-right, $x_0$ is where the probability increases the quickest, and $w$ is the “transition width”.

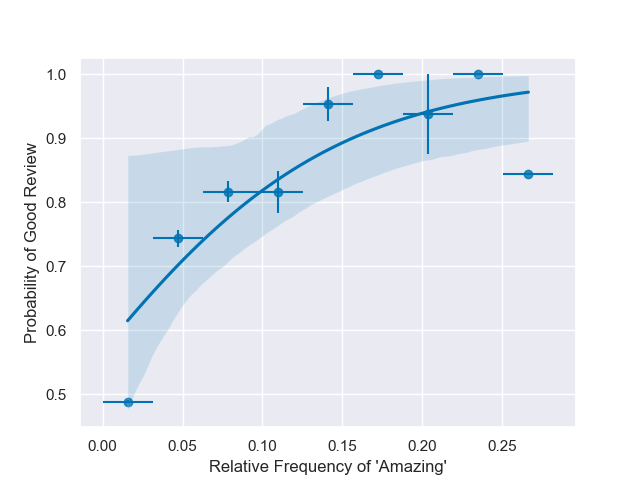

With lots of data you expect to find a distribution similar to this logistic function when plotting the probability of a good review versus the relative frequency of a particular word appearing

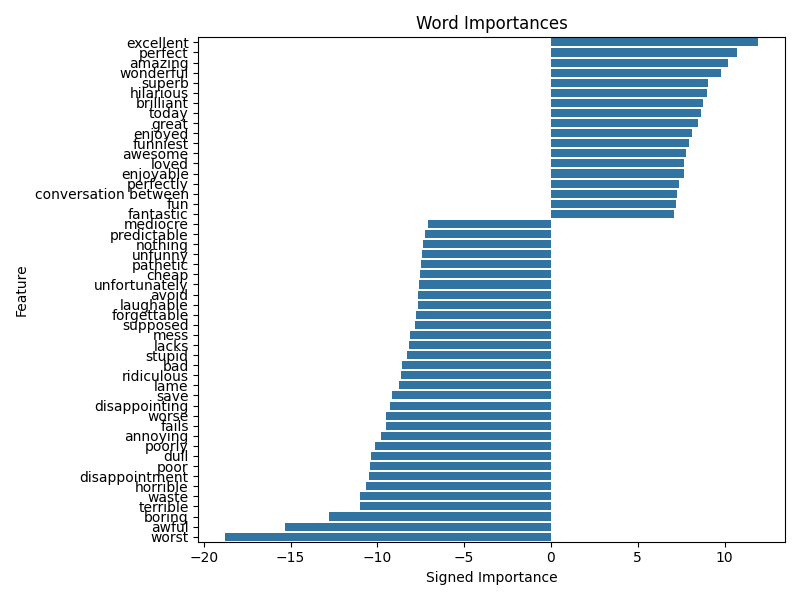

The scikit-learn Logistic Regression fits these types of curves for all the tokenized words that appear in the 50K reviews. Below are the inverse widths associated with the top 50 most-frequent words – negative widths make a word more likely to be associated with a negative review. Inverse widths may be interpreted as a word’s “importance” to the model, where a large importance (positive or negative) greatly affects the probability that the model will interpret a review as good or bad.

With the dataset I’ve been given, after training on 80% of the data, the model is 90.6% accurate on the withheld 20% of the data. Performance is slightly worse compared to when the TfidfVectorizer was used to bag the words (91.6%), but since I’m constrained by the server configuration (and money) I think it’s a reasonable hit in performance considering the performance improvement.

3. Deploying the Model

I followed this blog post by Tanuj Jain to get the model running on Flask. Flask warns me that I shouldn’t be using it as a production server, but I couldn’t see an easy way to set up a proper WSGI server so I’m sticking with Flask for now. I set up two routes for outside access: a landing page at the root of the server ‘/’ and a ‘/predict’ route. When you send a POST request to ‘/predict’, the message content you send is a review, and the received message contains a simple Good/Bad rating for the review.

The blog post then continued with setting up Docker. My local repos are all on Windows so I had to download Docker Desktop, which takes up a whole lot of CPU cycles when you first boot it up.

I then spooled up an AWS EC2-instance (which is surprisingly easy to get going), and downloaded docker with yum install docker. Don’t forget to start Docker with sudo systemctl start docker! I then uploaded the required Dockerfile, Python app, requirements.txt, and pickled models. I like using WinSCP for my SFTP purposes. Finally after docker build and docker run, my model is accessible with a simple curl command!

curl.exe -X POST http://ec2-18-216-26-152.us-east-2.compute.amazonaws.com/mrs_demo/request -H ‘Content-Type: application/json’ -d ‘This is a review. The movie was bad. The end.’

4. Interactive Demos

When you want to show something cool to people, I find it fairly rare that they have a command line available in the moment. I’d rather people be able to navigate to my GitHub pages site, explore to the demos section, and try out the tool. I tried for a while to have the demo hosted on the GitHub pages site itself, but https makes everything a nightmare. So I’ve simply linked to the EC2 server from GitHub pages, and augmented the landing page on the home ‘/’ route with some basic html and JavaScript to send POST requests to the ‘/predict’ route.

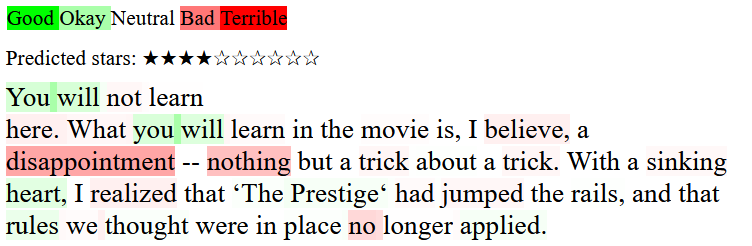

But getting a simple Good/Bad back from the model is no fun! I wanted to show why the model though it was a good or bad review. Since the model was already taking the entire review and rating it, it’s a simple task to ask the model to tokenize each single- and double-word in the review string, then ask the LinearRegression model for the “Importance” of that token. Since positive importances are associated with words that are more likely to give good reviews, these positive importances are colored green with a saturation equal to the importance over the maximum importance. Negatively important words are similarly colored red. And the color in the whitespace between each word represents the importance of the bigram formed from the two words.

Conclusion

The bag-of-words model I’ve used is obviously very naive, especially compared to the transformer models that are so popular nowadays. If I were doing this professionally I’d probably try importing the RoBERTa model, but since this model is already 650MB large, I’d need to scale up the server size just a tad.

Tags: #natural #language #processing #NLP #python #bag #of #words